Fleas: What They Are, What To Do

There are over 2,000 described species of fleas in the world. The most common domestic flea is the cat flea (Ctenocephalides felis felis).

The dog flea (Ctenocephalides canis) appears similar to the cat flea, but is rare in the United States. The sticktight flea (Echidnophaga gallinacea) can become a problem if pets frequent areas associated with poultry.

Eggs are oval, and smooth . They are tiny (0.5mm), but visible to the naked eye. Their white color may prevent them from being seen on lightly colored fabric. Small wormlike larvae (1.5-5 mm in length) hatch from the eggs. They are also visible to the naked eye.

They are eyeless, legless and sparsely covered with hairs. The larval body is translucent white with a dark colored gut that can be seen through the skin. These immature fleas will eventually spin silken cocoons in which they will develop (pupate) into adult fleas. Cocoons are sticky, attracting dirt and debris.

This camouflage may prevent them from being seen. Adults are about 1-3 mm in length, reddish-brown to black, wingless, and laterally compressed Their powerful hind legs are well adapted for jumping and running through hair and feathers.

Flea Life Cycle & Biology

Cat flea adults, unlike many other fleas, remain on their host. Females require a fresh blood meal in order to produce eggs, and they can lay up to 1 per hour! The smooth eggs easily fall from the pet onto the carpet, bedding, or lawn.

Adult fecal matter consists of relatively undigested blood. This dried blood also falls from the pet and serves as food for the newly hatched larvae. The young fleas will hatch within 2 days and feed on dandruff, grain particles, and skin flakes found on the floor around them, in addition to the fecal matter provided by adult fleas.

They prefer to develop in areas protected from rainfall, irrigation, and sunlight, where the relative humidity is at least 75% and the temperature is 70-90F. The larval stage lasts 5-15 days.

Flea life cycle.

Larvae spin silken cocoons within carpet fibers, floor crevices, or protected outdoor areas in which they will develop (pupate) into adult fleas. The cocoons are sticky and easily camouflaged by local debris. Under optimal conditions, new adults are ready to emerge within 2 weeks. They develop faster at higher temperatures, but can remain in their cocoons up to 12 months. Vibrations and/or an increase in carbon dioxide stimulate adults to emerge. Adults live 4-25 days and are the only stage that lives on the pet and feeds on fresh blood.

The cat flea is capable of transmitting plague and murine typhus to humans, but reports of such are rare; its primary importance is its nuisance to humans and pets. They are not picky about their meals; any warm-blooded animal will do. Bites usually cause minor itching, but may be more irritating to those with sensitive skin. Some people and pets suffer from flea allergy dermatitis, lasting up to 5 days and characterized by intense itching, reddening at the bite site, hair loss, and secondary infection.

Cat fleas also serve as intermediate hosts of the dog tapeworm (Dipylidium caninum). This intestinal parasite is transmitted to the pet while grooming via ingestion of an adult flea carrying a tapeworm cyst. The flea is infected by ingestion of the cyst during its larval stage. The parasite segments resemble small pieces of rice and may be discovered around the anal region of your pet.

Effective control requires eradication of fleas from the pet, the home, the yard, and control of the flea life cycle. Removal of fleas from the pet alone is futile; immature fleas (eggs, larvae, pupae) develop off the pet and new adults simply jump on, causing subsequent reinfestation.

New and safe products are available that can be used as part of a reduced chemical control program. There are also ways of making the environment less suitable for flea development.

Flea control is a three part process:

Removing fleas from pets may be done by a veterinarian, grooming parlor, or by the pet owner on the day of treatment, either before or while the premises are being treated. A flea comb may be used, but is not very effective for removing fleas; only 10-60% will be collected. Fleas should be dropped in soapy water and then discarded. This method is very time consuming, though, and most pet owners prefer to shampoo their pets.

Shampooing your pet removes the dried blood and skin flakes that fall to the ground and serve as food for flea larvae. The animal's body must be thoroughly lathered, and it is recommended that the lather remain for up to 15 minutes before the pet is rinsed.

Flea shampoos contain various insecticides: Pyrethrins are derived from the chrysanthemum plant and kill fleas on the animal quickly. Pyrethroids are synthetically derived from pyrethrins and have better residual action. Both of these are usually enhanced with piperonyl butoxide, a compound which will inhibit the fleas from metabolically changing the insecticide into nontoxic, excretable compounds. Carbamate insecticides are also available for use in shampoos. Citrus peel derivatives, such as D-limonene, are also added to shampoos and are fairly mild, making them excellent for use on puppies andkittens, as well as in households with infants. Some pets however, especially cats, may exhibit allergic reactions to this type of product. Pennyroyal oil, another natural product, is also available in shampoos. Pulegone, the active ingredient in this oil, has dose related toxicity to mammals and may induce lethargy, vomiting, diarrhea, nose bleeds, seizures, and, possibly, death due to liver failure. There is no antidote to pulegone poisoning . Label directions and cautions should be carefully followed when using this type of product. Mixing your own shampoo with pure oil is not recommended.

The newest advances in topical flea control applications are imidacloprid (Advantage) or fipronil (Frontline). Both are available as spot-on oils which are applied to the shoulder area of the pet and distribute over the body within a few hours. They are non-toxic to mammals and kill almost all fleas on the pet within 24 hours of treatment. Dogs and cats treated with imidacloprid have approximately 95% control for 3 weeks and then 80% control the fourth week. Fipronil kills 98% of the fleas on dogs and cats for 4 weeks, and efficacy continues for up to 8 weeks on dogs, but drops down to 80% protection on cats by sixth week. Fipronil also kills ticks on the animal for up to one month. If your pet displays flea allergy dermatitis take note: approximately 90% of the fleas on pets treated with either product fed (bit the pet) before their death. These fleas were also able to produce viable eggs. This means that while these products help reduce the symptoms of flea allergy dermatitis by killing fleas and reducing the number of flea bites on the animal, there may still be some allergic reaction because fleas are able to bite before dying. This blood meal will also enable them to reproduce.

Insect growth regulators (IGRs) and insect development inhibitors (IDIs) work by interfering with egg development and molting of adolescent fleas. They control the flea life cycle but do not kill adult fleas. Methoprene (Precor) and pyriproxyfen (Nylar, Archer) are IGRs available for pet treatment in sprays and flea collars. Lufenuron (Program), an IDI, is orally administered to the pet. These products do not take immediate effect because they target flea eggs and larvae. Use of one of these products along with use of Advantage or Frontline will kill adults and prevent development of immature fleas.

Scientific evidence regarding dietary supplementation with vitamin B, Brewer's yeast, or garlic suggest these methods are of little value.

Ultrasonic flea collars have also been proposed for use to keep fleas off pets, but are completely ineffective. Insecticidal flea collars also are not very effective.

Indoor treatment should be concentrated on areas frequented by your pets; this is where most of the eggs and larvae will be located. Vacuum the entire house and dispose of the vacuum bag immediately there will be developing fleas inside! Vacuuming will remove flea eggs and stimulate new adults to emerge from their cocoons, exposing them to any insecticide residue on the floor. Also, vacuuming may not pick up any larvae due to their ability to wrap around and hold on to carpet fibers. Steam cleaning carpets is even more effective than normal vacuuming and should be considered if infestation is severe. Wash pet's bedding and throw rugs. Sprays or foggers containing an insecticide and insect growth regulator should be applied according to label directions after vacuuming. Borate carpet treatment, applied either by the homeowner or a professional exterminator, works as intestinal poison upon ingestion by flea larvae. The powder is sprinkled and worked into the carpet. Overall risk of danger to pets and humans is unknown, but appears to be low. This treatment, however, is not recommended for homes with infants. Diatomaceous earth has also been used as a chafing agent to control larvae in carpets, but it contains silica which is known to cause lung disease in humans if inhaled in excessive quantity.

Light traps placed around the home, especially where the pet frequents, may collect fleas upon emergence from their cocoons. Adult fleas have been noted to orient themselves toward light and jump when light is interrupted, as though the shadow signals passing of an unsuspecting host. Tests indicate they prefer yellow-green light (525nm) that remains on for 10 minutes and flashes off for 5 seconds. However, it is doubtful that this trap will attract fleas off your pet.

Cedar chips and leaves from wax myrtles may have some repellent properties (some people swear by them!), but have not been scientifically proven.

Restrict pet access from areas that are hard to treat, such as children's playrooms, crowded garages or work areas.

Flea larvae develop in shaded, humid areas, but will drown in a flooded environment. Rainfall is often enough to curb larval development outdoors. In addition to drowning, the fecal dried blood meal provided by adult fleas is no longer available if the lawn is wet. Loose debris and weeds should be removed and the lawn mowed to expose their environment. Sprays containing insecticides registered for outdoor use, such as pyrethroids, may be applied during dry seasons every 2-3 weeks to shaded areas where pets frequent. Insect growth regulators are also available for outdoor use. Pyriproxyfen (Archer, Nylar) is the most effective outdoor treatment; it is very stable and provides protection against developing fleas for approximately 7 months. Methoprene (Siphotrol, Precor) is also commonly used outdoors, but is not stable in sunlight. Larvae prefer shaded dry areas, so spraying the entire yard is wasteful and irresponsible. If possible, control access of feral animals (opossums, skunks, etc.) to your yard as they bring new fleas with them.

Sheds and dog houses should be treated the same as the house. Biological control using the beneficial nematode Steinernema carpocapsae has been investigated in several areas around the United States. These nematodes are applied to the lawn as a spray and destroy the flea larvae (and other insects) by parasitizing them. They do not attack people, pets, or plants. This treatment should reduce flea populations if label directions are carefully followed. In fact, just spraying the yard with water is enough to reduce flea populations! The nematode treatment is probably not needed.

Restricting pet access from areas that are difficult to treat (e.g., beneath porches, inside crowded sheds) may also help flea control.

Detection is as simple as seeing fleas on your pet, noticing your pets scratching, or flea bites around your ankles. Perhaps there are small black pieces of dirt covering your pet's bedding, or perhaps you've noticed tapeworm segments near or on your pet. The black dirt is the adult flea feces left behind to serve as food for larvae, and tapeworms are transmitted by ingestion of fleas.

Monitoring is more difficult than simple detection. Fleas reproduce rapidly (one female can produce up to one egg per hour throughout her 4 week adult life), so if you spot one flea there are probably more. Combing your pet or wearing white socks around the house are also ways to determine severity of the infestation.

Q: My daughter gets bitten by fleas while I am never bothered. Why is this?

A: Blood feeding insects are attracted to chemicals emitted from the body (sweat, exhalation, etc.). Some people just smell more attractive than others to certain insects. Individual sensitivity to the bite is another reason. To some, flea bites are extremely irritating while other people hardly notice them. This is caused by an allergic response to the flea saliva and occurs in varying degrees among people.

Q: I have bombed my house for fleas three times this month and still have them. Why?

A: It is likely that you are seeing adults emerge from cocoons that were produced before you bombed. The cocoons are deep within the carpet and treatment may not have reached them. If you did not treat your yard new fleas may be coming indoors on you or your pets. If the foggers you used contained pyrethrins or pyrethroids, you probably only killed larvae and adults. Insect growth regulators are available in foggers and will prevent development of immature fleas.

Q: I just moved into a new apartment. It is infested with fleas. Where did they come from and what can I do?

A: The people living there before you probably had a pet. Even if the apartment was treated with insecticides before you moved in, the treatment may not have penetrated the carpet to kill developing pupae. Treatment is described above.

Q: When we go on vacation, we board our dogs at the kennel and leave the house closed up for three weeks. As soon as we get home we are attacked by fleas. The dogs have been away. What is going on?

A: The fleas that were in the egg and larval stage have pupated and matured and were waiting in their cocoons for the proper stimulation to emerge (vibration, carbon dioxide). In order to keep this from happening, next time treat your home with an insecticide that kills adult fleas and an insect growth regulator to prevent immature fleas from developing.

Q: What is the difference between dog fleas and cat fleas?

A: Cat fleas are the main flea on both cats and dogs in North America. Dog fleas are found in Europe. They are distinguished by a slight morphological difference which is only detectable under high magnification.

Q: What are sand fleas?

A: "Sand fleas" or "beach fleas" are common names for small orange amphipods found along the beach. They are distant relatives of true fleas, and are not even insects (they have more than six legs). Also, some people may refer to fleas that just happen to be developing in sandy areas as "sand fleas".

1. This document is ENY-291, one of a series of the Entomology and Nematology Department, Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida. First published: March 1997. Revised: July 2007. Please visit the EDIS Website at http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu.

2. D. L. Richman, graduate assistant, and P. G. Koehler, professor, Department of Entomology and Nematology, Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida, Gainesville, 32611.

Back to Top

Sometimes referred to as "red coats," "chinches," or "mahogany flats" (USDA 1976), bed bugs, Cimex lectularius Linnaeus, are blood feeding parasites of humans, chickens, bats and occasionally domesticated animals (Usinger 1966).

Bed bugs are suspected carriers of leprosy, oriental sore, Q-fever, and brucellosis (Krueger 2000) but have never been implicated in the spread of disease to humans (Dolling 1991). After the development and use of modern insecticides, such as DDT, bed bug infestations have virtually disappeared.

However, since 1995, pest management professionals have noticed an increase in bed bug related complaints (Krueger 2000).

Adult bed bug, Cimex lectularius Linnaeus

Human dwellings, birds nests, and bat caves make the most suitable habitats for bed bugs since they offer warmth, areas to hide, and most importantly hosts on which to feed (Dolling 1991). Bed bugs are not evenly distributed throughout the environment but are instead concentrated in harborages (Usinger 1966). Within human dwellings, harborages include cracks and crevices in walls, furniture, behind wallpaper and wood paneling, or under carpeting (Krueger 2000).

Bed bugs are usually only active during night but will feed during the day when hungry (Usinger 1966). Bed bugs can be transported on clothing, in traveler's luggage, or in bedding and furniture (USDA 1976) but lack appendages to enable them to cling to hair, fur, or feathers, so are rarely found on hosts (Dolling 1991).

The adult bed bug is a broadly flattened, ovoid, insect with greatly reduced wings (Schuh and Slater 1995). The reduced fore wings, or hemelytra, are broader than they are long, with a somewhat rectangular appearance. The sides of the pronotum are covered with short, stiff hairs (Furman and Catts 1970). Before feeding, bed bugs are usually brown in color and range from 6 to 9.5 mm in length. After feeding, the body is often swollen and red in color (USDA 1976).

The two bed bugs most important to man are the common bed bug, Cimex lectularius, and the tropical bed bug, Cimex hemipterus. These two species of bed bugs can easily be distinguished by looking at the prothorax, the first segment of the thorax. The prothorax of the common bed bug is more expanded laterally and the extreme margins are more flattened than that of the tropical bed bug (Smith 1973).

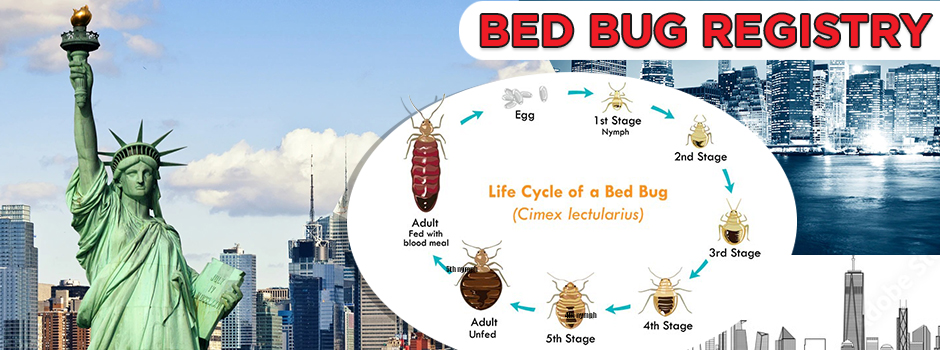

Because of their confined living spaces, copulation among male and female bed bugs is difficult. The female possesses a secondary copulatory aperture, Ribaga's organ or paragenital sinus, on the fourth abdominal sternum where spermatozoa from the male are injected. The spermatozoa then migrate to the ovaries by passing through the haemocoel, or body cavity (Dolling 1991). The female bed bug lays approximately 200 eggs during her life span at a rate of one to 12 eggs per day (Krueger 2000). The eggs are laid on rough surfaces and coated with a transparent cement to adhere them to the substrate (Usinger 1966). Within six to 17 days bed bug nymphs, almost devoid of color, emerge from the eggs. After five molts, which takes approximately ten weeks, the nymphs reach maturity (USDA 1976).

Bed bugs are most active at night, they are extremely shy and wary so their infestations are not easily located (Snetsinger 1997). However, when bed bugs are numerous, a foul odor from oily secretions can easily be detected (USDA 1976). Other recognizable signs of a bed bug infestation include excrement left around points of entry and exit to their hiding places (Dolling 1991) and reddish brown spots on mattresses and furniture (Frishman 2000). Good sanitation is the first step to controlling the spread of bed bugs. However, upscale hotels and private homes have recently noted infestations, suggesting that good sanitation is not enough to stop a bed bug infestation (Krueger 2000).

If bed bugs are located in bedding material or mattresses, control should focus on mechanical methods of control, such as vacuuming, caulking and removing or sealing loose wallpaper, to minimize the use of pesticides (Frishman 2000). The effectiveness of using steam cleaners or hot water to clean mattresses is questionable. Heat is readily absorbed by the mattress and does no harm to the bed bug in fact the moisture may produce favorable conditions for house dust mites. Pillows should be removed and dry-cleaned or replaced (Snetsinger 1997). For severe infestations, however, pesticides may be used. Care should be taken not to soak mattresses and upholstery with pesticides. Allow bedding and furniture to dry throughly before using.

For more information, see the Insect Management Guide for Bed Bugs (http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/IG083).

Dolling WR. 1991. The Hemiptera. Oxford University Press, New York, New York.

Fasulo TR. 2002. Bloodsucking Insects. UF/IFAS SW 156.

Fasulo TR, Kern W, Koehler PG, Short DE. 2005. Pests In and Around the Home. Version 2.0. UF/IFAS CD-ROM. SW 126.

Frishman A. 2000. Bed Bug basics and control measures. Pest Control 68:24.

Furman DP, Catts E. 1970. Manual of Medical Entomology, 3rd ed. National Press Books, Palo Alto, California.

Ghauri MSK. 1973. Hemiptera (bugs), pp. 373-393. In K.G.V. Smith [ed], Insects and other Arthropods of Medical Importance. British Museum, London, England. [USDA] U.S. Department of Agriculture. 1976. How to control bed bugs. USDA. Washington D.C.

Koehler PG, Hertz J. 2005. Bed bugs and blood-sucking conenose. EDIS. "http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/IG083 (9 December 2005).

Krueger L. 2000. Don't get bitten by the resurgence of bed bugs. Pest Control 68:58-64.

Potter, MF 2004. Bed Bugs. University of Kentucky Entomology FactSheets. http://www.uky.edu/Agriculture/Entomology/entfacts/struct/ef636.htm (9 December 2005).

Snetsinger R. 1997. Bed bugs & other bugs, pp. 393-425. In A. Mallis and S.A. Hedges [eds.], Handbook of Pest Control, 8th ed. Franzak & Foster Co., Cleveland, Ohio.

Schuh R, Slater JA 1995. True Bugs of the World (Hemiptera : Heteroptera) Classification and Natural History. Cornell University Press, Ithica, New York.

Usinger RL. 1966. Monograph of Cimicidae (Hemiptera - Heteroptera). Entomological Society of America, College Park, Maryland.

1. This document is EENY-140 (IN297), one of a series of Featured Creatures from the Entomology and Nematology Department, Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida. Published: June 2000. Revised: December 2005. Reviewed: March 2008. This document is also available on Featured Creatures Website at http://creatures.ifas.ufl.edu. Please visit the EDIS Website at http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu.

2. Shawn E. Brooks, Entomology and Nematology Department, University of Florida, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, Gainesville, FL 32611.

Back to Top

Ticks

Ticks are not insects, and are closely related to the spiders. Adult ticks have eight legs. All ticks are parasitic, feeding on the blood of animals.

Of the ticks found in Florida, the brown dog tick, and the American dog tick, are the most troublesome. The brown dog tick rarely bites humans, but infestations are frequently found on dogs and in the home. The American dog tick attacks a wide variety of hosts, including humans, but rarely will infest homes.

The brown dog tick seldom attacks animals other than dogs. It is most likely found where dogs are kept in or around the house. The brown dog tick is not known to transmit diseases to humans but may transmit disease among dogs.

The adult female tick lays a mass of 1000-3000 eggs after engorging on a dog's blood. These eggs are often found in cracks on the roof of kennels or high on the walls or ceilings of buildings. In the house, eggs are laid around baseboards, window and door casings, curtains, furniture, and edges of rugs. The egg-laying females are often seen going up walls to lay eggs.

The eggs hatch in 19-60 days into a six-legged, small seed tick. The seed tick takes a blood meal from dogs when they are available. The larvae are so small they won't be noticed on the dog unless a number are together. The seed tick remains attached for 3-6 days, turns bluish in color, and then drops to the floor. After dropping from the host, the seed tick hides for 6-23 days before molting into an eight-legged, reddish-brown nymph. It is now ready for another blood meal and again seeks a dog host. The nymphs attach to dogs, drop off, and molt to the adult in 12-29 days. As a reddish-brown adult, it again seeks a blood meal, becomes engorged, and is bluish in color, reaching about 1/3 inch in length.

Unengorged larvae, nymphs, and adults may live for long periods of time without a blood meal. Adults have been known to live for as long as 200 days without a blood meal. Indoors, ticks hiding between blood meals may be found behind baseboards, window casings, window curtains, bookcases, inside upholstered furniture, and under edges of rugs. Outdoors, ticks hide near foundations of buildings, in crevices of siding, or beneath the porch.

The American dog tick is also a common pest of pets and humans in Florida. The adult males and females are frequently encountered by sportsmen and people who work outdoors. Dogs are the preferred host, although the American dog tick will feed on other warmblooded animals. The nymphal stages of the American dog tick usually only attack rodents. For this reason the American dog tick is not considered a household pest.

The female dog tick lays 4000-6500 eggs and then dies. The eggs hatch into seed ticks in 36-57 days. The unfed larvae crawl in search of a host and can live 540 days without food. When a small rodent is found, the larvae attach and feed for approximately 5 days. The larvae then drop off the host and molt to the nymphal stage. The nymphs crawl about in search of a rodent host, attach to it, and engorge with blood in 3-11 days. Nymphs can live without food for up to 584 days.

Adults crawl about in search of dogs or large animals for a blood meal. Adults can live for up to 2 years without food. American dog tick adults and many other species can be found along roads, paths, and trails, on grass, and on other low vegetation in a "waiting position." As an animal passes by the tick will grasp it firmly and soon start feeding on its host. The males remain on the host for an indefinite period of time alternately feeding and mating. The females feed, mate, become engorged, and then drop off to lay their eggs.

The American dog tick requires from 3 months to 3 years to complete a life cycle. It is typically an outdoor tick and is dependent on climatic and environmental conditions for its eggs to hatch.

When feeding, ticks make a small hole in the skin, attach themselves with a modification of one of the mouthparts which has teeth that curve backwards, and insert barbed piercing mouthparts to remove blood.

The presence of ticks is annoying to dogs and humans. Heavy continuous infestations on dogs cause irritation and loss of vitality. Pulling ticks off the host may leave a running wound which may become infected because of their type of attachment.

The brown dog tick is not a vector of human disease, but it is capable of transmitting canine piroplasmosis among dogs.

The American dog tick may carry Rocky Mountain spotted fever, tularemia, and other diseases from animals to people. Dogs are not affected by these diseases, but people have become infected by picking ticks from dogs. People living in areas where these wood ticks occur should inspect themselves several times a day. Early removal is important since disease organisms are not transferred until the tick has fed for several hours.

The American dog tick is also known to cause paralysis in dogs and children where ticks attach at the base of the skull or along the spinal column. Paralysis is caused by a toxic secretion produced by the feeding tick. When the tick is removed, recovery is rapid, usually within 8 hours. Sensitized animals may become paralyzed by tick attachment anywhere on the body.

Lyme disease is transmitted by ticks, but few cases have been reported in Florida. Most transmission occurs in the New England states, and the primary vector is the deer tick. The deer tick is not prevalent in Florida, but species that are close relatives and are capable of transmitting Lyme disease are common throughout the state. The American dog tick and the brown dog tick are not considered important vectors of Lyme disease. In cases of tick bites where Lyme disease is suspected, a physician should be contacted so that appropriate blood tests can be done for the patient.

Ticks should be removed from pets and humans as soon as they are noticed. Ticks should be removed carefully and slowly. If the attached tick is broken, the mouthparts left in the skin may transmit disease or cause secondary infection. Ticks should be grasped with tweezers at the point where their mouthparts enter the skin and pulled straight out with firm pressure. A small amount of flesh should be seen attached to the mouthparts after the tick is removed.

People entering tick infested areas should keep clothing buttoned, shirts inside trousers, and trousers inside boots. Do not sit on the ground or on logs in bushy areas. Keep brush cleared or burned along frequently traveled areas. Repellents will protect exposed skin or clothing. However, ticks will sometimes crawl over treated skin to untreated parts of the body.

Pesticidal control of ticks may require both pet treatment and treatment of the infested area. If a heavy tick infestation occurs it is necessary to treat pets, home, and yard at the same time. Established brown dog tick infestations of homes and yards are frequently difficult to control.

Pets should be treated by using dusts, dip or sprays. Rub dusts into the fur to the skin being careful not to allow chemicals to get into the eyes, nose, or mouth. Heavy infestations of ticks on the animal should be controlled by spraying or dipping. See your veterinarian for products and recommendations for direct pet treatment.

Footnotes

1.This document is ENY-206, one of a series of the Entomology and Nematology Department, Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida. Publication date: June 1991. Revised: February 2003. Please visit the EDIS Website at http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu. Additional information on these organisms, including many color photographs, is available at the Entomology and Nematology Department website located at http://entnemdept.ifas.ufl.edu.

Go here to see the original:

Fleas, Ticks, Bed Bugs Exterminator Pest Control Company ...

Residence

Residence  Location

Location