Have you ever wondered which animals getfreakiest between the sheets?

The answer to that is, literally, probably bed bugs.

But what about octopus? Why do lobsters shoot urine from their faces? And what is "penis fencing"?

If these are the questions keeping you up at night, read on.

The sport of fencing where opponents spar using modified swords or "foils" is thought to have emergedaround the 14th or 15th centuries.

But in nature, it's existedfar longer.

Pseudobiceros is a genus of flatworm flat, soft-bodied,aquatic animals that also engagesin fencing.

But unlike the human sport, flatworms don't use "foils". They use their penises.

The other difference is thatin"penis fencing", the loser ends up pregnant.

Pseudobicerosare hermaphrodites the majority of the body mass of species like the Persian carpet flatworm (Pseudobiceros bedfordi) comprises both testes and ovaries.

During battle, each assailant exists as a kind of Schrdinger's flatworm, whereinbothanimalsare simultaneously the potential father andmother.

The first penetration decides their fate.

A successful strikealmost anywhere on the bodysees sperm injected into the skin, where it will migrate through pores tofertilise the eggs of the disappointed mother-to-be.

Once the deed is done, the "father"exits the scene to fence again, while the expectant mother will gestate their unwelcomeclutchfor around 10 days.

In the world of flatworms,carrying fertilised eggs is laborious, and gestation putsa temporary hiatus on seeking opportunities to further spreadone's genes. So flatworms will fight ferociously to avoid that fate.

Here's a sentence you probably didn't think you'd read today: female lobsters urinate out ofholesin their faceto show a male they're interested in mating.

And that's only the start of their freakiness.

The urine, which is expelled from holes known as nephropores at the base of the lobsters' second antennae, contain pheromones to convey her gender and potentialsuitability as a mate.

"They have theseremarkable,weirdly orientated organs which arethe equivalent of our kidneys basically," says Tomer Ventura, a scientist working in crustacean aquaculture at the University of the Sunshine Coast.

"They're situated pretty much in theircheeks under the antennae."

Dr Ventura, who has pioneeredgene-silencing technology that can be used in commercial aquaculture to produce a single-sex population of crustaceans, says thatin wild lobsters, the dominant male sits in a den from where he vets potential suitors.

To make sure he cops a full blast of the spicypheromone mix, the female uses her gills to create a current, wafting it in his general direction.

"She squirts her urine directly into the den where the dominant male is," Dr Ventura says.

If he's picking up what she's putting down, she'll be invited inside, where he'll provide protection whilesheremoves her carapace her shell replacing it with a fresher, cleaner model.

The courting ritualhas mostly been studied in the American lobster, Homarus americanus, and while it might be the sort of behaviour you'd expect from American crustaceans, it's also true of our own spiny lobster, among others, Dr Ventura says.

He says in lobsters, the male produces a spermatophore a capsule of sperm, which also contains a protective gelatinous matrixthat sets like a sticky concrete on contact with water.

The female carries that spermatophore around with her until she's ready to release her eggs.

"The female releases virtually millions of eggs while scraping the surface of the spermatophore to reveal the intact sperm.

"[At the same time she's]curling her tail to release that cement that sticks the fertilised eggs onto her swimming legs in the tail."

At this point it's probably safest toassume there'surine involved unlessstated otherwise.

In the case of giraffes, males will smell the hindquarters of the female, often flaring his upper lip in what is known as a "flehman response".

While it has the appearance of a grimace, the flehman response draws air into the vomeronasal organ an olfactory sense organ in the nasal cavity above the roof of the mouth which assists in the detection ofpheromones.

He's checking to see if she's ovulating and ready to mate.

But if he's not convinced, the male will encourage her to urinate by rubbing her hindquarters.

He'll then taste her urine, and if he picks up the signals he's after, will follow her around in the hopes of mating.

In the wild, he won't be the only one showing an interestthough, and will need to fight off other males using his huge neck to pummel his rivals, while attempting to plunge his ossicones horn-like appendages on his head into their flesh.

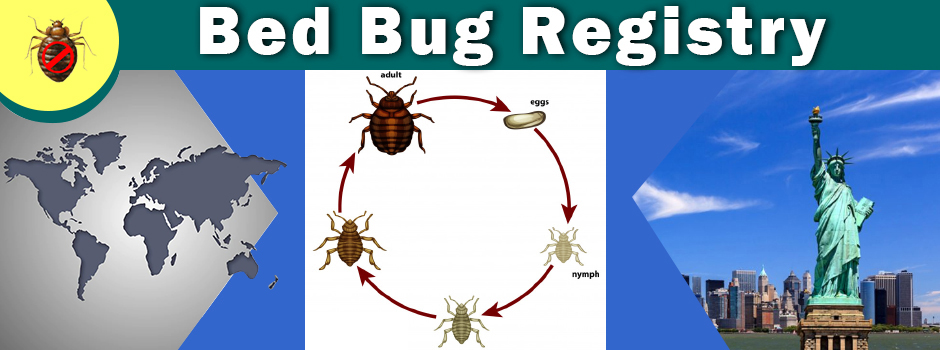

If you've ever had bed bugs and thought, "gross, I'm sharing my bed with bugs", strap in.

Humans and bed bugs have a long history.

Research suggests bed bugs were originally bat specialists, feeding on the winged creatures in caves in Africa.

But as our ancestors moved into caves millions of years ago, bed bugs decided we were a tastier option and shifted their allegiance.

As humans spread from Africa and across Eurasia, we took the bed bugs with us.

We can't really begrudge the bed bugs for feeding on our bloodthough. They need all the energy they can get formating.

Adult bed bugs become most active during witching hour between about midnight and 5am.

They locate their sleeping hosts by detecting exhaled CO2 and body heat, and once fed, are in the mood for love.

Cue Barry White? Not quite.

The male bed bug stabs his reproductive organ through the right side of the female's body wallinto what is called her Organ of Berlese.

The male's sperm enters the body cavity, migrates to her ovaries and fertilises her eggs.

Females may be stabbed multiple times by different males during one outing, and will retreat to recover, lesttheir traumatic mating prove fatal.

How many eggs and offspring she is capable of producing depends on how much blood of yours she's able to consume in her lifetime of between 100 and 300 days.

Of course octopus are on the list. They've got eight legs, nine brains and only a year or so to use them.

Research has observed at least one female octopus strangling her partnerduring copulation.

Another study observed a smallmale Octopus cyanea, also known as big blue octopus, mating with a larger female 12 times over a three-and-a-half-hour period while she foraged for food in Palau, Micronesia.

Perhaps fed up, hungry or both, on his 13th attempt, she suffocated him, took him back to her den, and "spent two days cannibalising him".

Michael Amor, a research assistant in the aquatic zoologydepartment at the Western Australian Museum,says it's probably not a great surprise that octopus sometimes eat their mates.

"They're not the most social beings. Theremight not be that [emotional] barrier to feeling you shouldn't eat your neighbour," Dr Amor said.

Research published last yearalso showed female octopuses throwing shells and other debris at males to ward off their unwanted advances.

It probably makes sense that a female should be discerningabout whofathersher children. It's typically her only shot at reproduction, and the egg-brooding period can be especially traumatic.

For most shallow-water octopus species, once the deed is done the female sits on her eggs for a period of one to three months.

Even in these instances, females have been known to eat their own arms rather than leave the nest in search of food, according to Dr Amor.

But in deeper water, where conditions areharsher and colder, thingscan stretch out much longer.

Back in 2014, research published in PLOSdetailed the exploits ofa female deep-sea octopus Graneledone boreopacifica in 1,397 metres of water on a sloping wall in the Submarine Canyon off central California.

Using a remotely operated vehicle, scientists first encountered the female over a period of a few weeks, first without eggs and then shortly after having laid them.

Seizing the opportunity to measure the brooding time of a deep-sea octopus, the researchers endeavoured to monitor how long she sat on her clutch.

Four years later, they were still watching.

The eggs had continued to grow, whilst she was diminishing in size and had becomepale, with cloudy eyes and slack skin.

On the researchers'final visit, after 53 months, only the "tattered remnants of empty egg capsules" remained in her place.

It was the longest-known egg-brooding period for any animal.

Olaf Meynecke spent years researching mud crabs and says after what he's seen, he can no longer eat the feistycrustaceans.

For Dr Meynecke, a marine ecologist at Griffith University who now studies whales, it wasn'tso much how they mate as what they eat.

"They're literally turning rotten meat into their own meat, whichwe then love to eat," he says.

On the bow-chicka-wow-wowscale, mud crabs are about mid-range, but there's some research, including some conducted by Dr Meynecke,that earns them the final place on this list.

Typically mud crabs hang around coastal, mangrove-lined waterways in the tropics and sub-tropics.

When it comes to mating, the male jumps on top of the female, and will basically hitch a ride around with her for a few days.

In some instances, the males have been known to pick up moulted females and carry themaroundfor several days while mating.

Similar to lobsters, the male deposits a spermatophore capsule that the female carries with her until she's ready to fertilise her eggs.

Not known to be great long-distance swimmers, the females typically hang around their estuaries for most of their life cycle.

Want more science plus health, environment, tech and more? Subscribe to our channel.

However, some large, gravid females have been found 50 kilometres or more offshore.

Dr Meynecke's team wanted to see if they were returning back to their estuaries after such an epic journey.

"Wetaggedsomeof those females in the Logan River [in south-east Queensland]," he said.

"They were acoustic tags about $800 tags on eachcrab."

Unfortunately for Dr Meynecke's hip pocket, the crabs never returned.

The hypothesis is thata certain proportion of older females crabs make a one-way journey for a final reproductive effort, culminating in the release of their fertilised eggs into the East Australia Currentto disperse their genes far and wide.

Get all the latest science stories from across the ABC.

Read the original here:

The weirdest and wildest mating rituals in the animal world, from bed bugs to giraffes - ABC News

Residence

Residence  Location

Location

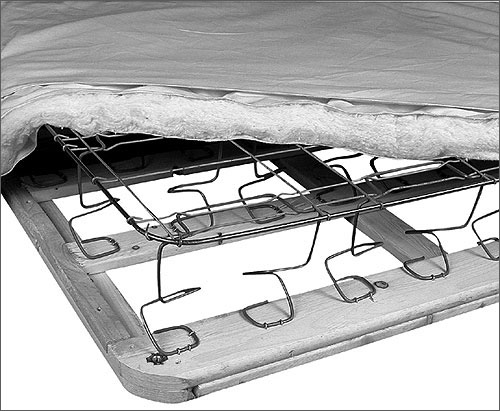

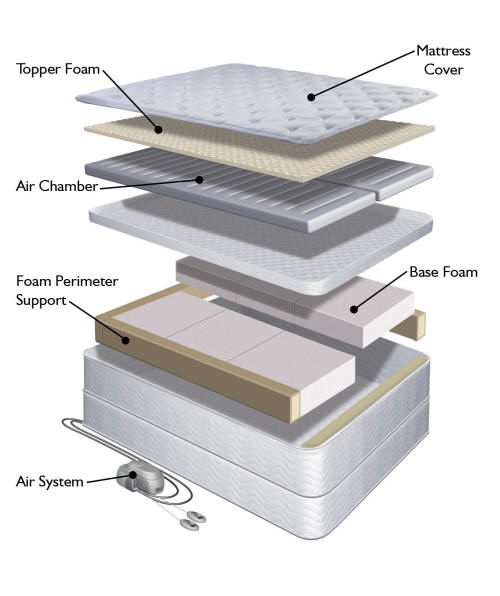

Encasing mattress and box springs in impermeable bed-bug-bite-proof encasements after a treatment for an infestation is an alternative treatment which works better and is more comfortable whereas wrapping bedding in plastic causes sweating. Box springs afford many places for bed bugs to hide, especially underneath where the fabric is stapled to the wooden frame. Oftentimes the underlying gauze dust cover must be removed to gain access for inspection and possible treatment. Successful treatment of mattresses and box springs is difficult, however, and infested ones may need to be discarded or encased in a protective cover. Cracks and crevices of bed frames should be examined, especially if the frame is wood. (Bed bugs have an affinity for wood and fabric more so than metal or plastic). Headboards secured to walls should also be removed and inspected. In hotels and motels, the area behind the headboard is often the first place that the bugs become established. Bed bugs also hide among items stored under beds.Some pest control firms want furniture moved away from walls and mattresses and box springs stood on edge before they arrive; others prefer to inspect first and move these items themselves. Since bed bugs can disperse throughout a building, it often will be necessary to inspect adjoining rooms and apartments.

Encasing mattress and box springs in impermeable bed-bug-bite-proof encasements after a treatment for an infestation is an alternative treatment which works better and is more comfortable whereas wrapping bedding in plastic causes sweating. Box springs afford many places for bed bugs to hide, especially underneath where the fabric is stapled to the wooden frame. Oftentimes the underlying gauze dust cover must be removed to gain access for inspection and possible treatment. Successful treatment of mattresses and box springs is difficult, however, and infested ones may need to be discarded or encased in a protective cover. Cracks and crevices of bed frames should be examined, especially if the frame is wood. (Bed bugs have an affinity for wood and fabric more so than metal or plastic). Headboards secured to walls should also be removed and inspected. In hotels and motels, the area behind the headboard is often the first place that the bugs become established. Bed bugs also hide among items stored under beds.Some pest control firms want furniture moved away from walls and mattresses and box springs stood on edge before they arrive; others prefer to inspect first and move these items themselves. Since bed bugs can disperse throughout a building, it often will be necessary to inspect adjoining rooms and apartments.

Affording access for inspection and treatment is essential, and excess clutter should be removed. In some cases, infested mattresses and box springs will need to be discarded. Since bed bugs can disperse throughout a building, it also may be necessary to inspect adjoining rooms and apartments .Encasing mattress and box springs in impermeable bed-bug-bite-proof encasements after a treatment for an infestation is an alternative treatment which works better and is more comfortable whereas wrapping bedding in plastic causes sweating.

Affording access for inspection and treatment is essential, and excess clutter should be removed. In some cases, infested mattresses and box springs will need to be discarded. Since bed bugs can disperse throughout a building, it also may be necessary to inspect adjoining rooms and apartments .Encasing mattress and box springs in impermeable bed-bug-bite-proof encasements after a treatment for an infestation is an alternative treatment which works better and is more comfortable whereas wrapping bedding in plastic causes sweating.