Bed Bugs Facts and Information

The bed bug database is an international bed bug registry database with maps to provide people with a search and submit tool on every page of the site to see and report up to date bed bug infestations. The site will also provide excellent information on how to inspect, prepare, and eradicate bed bugs for the long term.

Bed bugs travel by hitch hiking on luggage, people and furniture - even worse, bedbugs can walk from apt. to apt and house to house, neither residential or commercial space is safe from these blood sucking parasites. Hotels are the ones being hit the hardest these days as you can imagine because of the high turnover of people staying at these places.

Cleanliness has nothing to do with bed bugs spreading or infesting places, because they absolutely do not discriminate and treating bed bugs is very difficult because they have evolved to become highly resistant to many pesticides and are practically immune to over the counter products. Never try to solve or treat your bed bug problem without professional help. Contact us and we would be happy to provide you with free bed bug information from one of our bed bug specialists, we can direct you to bed bug experts in your local area who can help you solve this menace.

Different Types Of Bed Bugs

The common bedbug (Cimex lectularius) is the species best adapted to human environments. It is found in temperate climates throughout the world. Other species include Cimex hemipterus, found in tropical regions, which also infests poultry and bats, and Leptocimex boueti, found in the tropics of West Africa and South America, which infests bats and humans. Cimex pilosellus and Cimex pipistrella primarily infest bats, while Haematosiphon inodora, a species of North America, primarily infests poultry.

Bedbugs can survive a wide range of temperatures and atmospheric compositions. Below 16.1 °C (61 °F), adults enter semi-hibernation and can survive longer. Bedbugs can survive for at least five days at 'ˆ’10 °C (14 °F) but will die after 15 minutes of exposure to 'ˆ’32 °C ('ˆ’25.6 °F). They show strong resistance to dessication, surviving low humidity and a 35'“40°C range even with loss of one-third of body weight; earlier life stages are more susceptible to drying out than later ones. The thermal death point for C. lectularius is high: 45 °C (113 °F), and all stages of life are killed by 7 minutes of exposure to 46 °C (115 °F). Bedbugs apparently cannot survive high concentrations of carbon dioxide for very long; exposure to nearly-pure nitrogen atmospheres, however, appears to have relatively little effect even after 72 hours.

Biology

There are 6 recognized subfamilies of Cimicidae and up to 23 genera, while the number of species has been given as anywhere from 75 to 108.

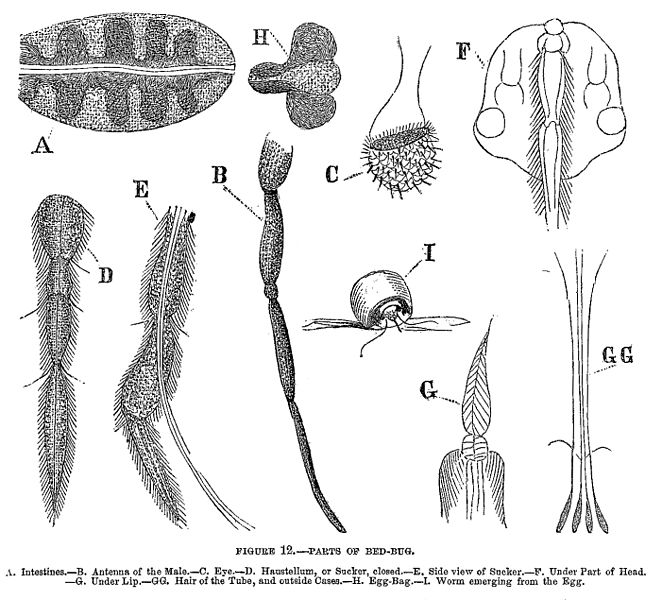

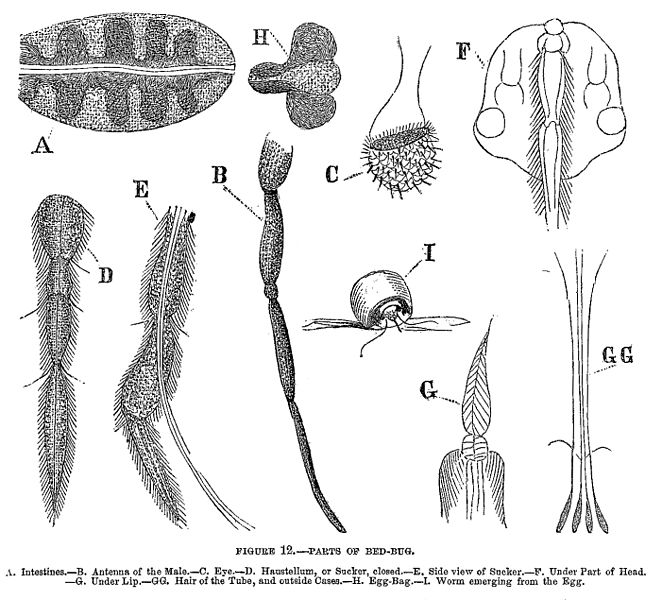

Adult bedbugs are reddish-brown, flattened, oval, and wingless. Bedbugs have microscopic hairs that give them a banded appearance. Adults grow to 4'“5 mm in length and 1.5'“3 mm wide. Newly hatched nymphs are translucent, lighter in color and become browner as they moult and reach maturity.

Bedbugs use pheromones and kairomones to communicate regarding nesting locations, attacks, and reproduction. The life span of bedbugs varies by species and is also dependent on feeding.

Feeding habits

Bedbugs are obligatory hematophagous (bloodsucking) insects. Most species only feed on humans when other prey are unavailable. They are normally out at night just before dawn, with a peak feeding period of about an hour before sunrise, but have been observed feeding during the day. Bedbugs are attracted to their hosts primarily by carbon dioxide, secondarily by warmth, and also by certain chemicals. They reach a detected host by crawling, or sometimes dropping from a height.

A bedbug pierces the skin of its host with two hollow feeding tubes. With one tube it injects its saliva, which contains anticoagulants and anesthetics, while with the other it withdraws the blood of its host. After feeding for about five minutes, the bug returns to its hiding place.

A bedbug pierces the skin of its host with two hollow feeding tubes. With one tube it injects its saliva, which contains anticoagulants and anesthetics, while with the other it withdraws the blood of its host. After feeding for about five minutes, the bug returns to its hiding place.

Although bedbugs can live for a year without feeding, they normally try to feed every five to ten days. When it's cold, bedbugs can live for about a year; at temperatures more conducive to activity and feeding, about 5 months.

At the 57th Annual Meeting of the Entomological Society of America in 2009, it was reported that newer generations of pesticide-resistant bedbugs in Virginia could survive only two months without feeding.

Predators

Natural enemies of bedbugs include the masked hunter (AKA "masked bedbug hunter"), cockroaches, ants, spiders, mites, and centipedes. The Pharaoh ant's (Monomorium pharaonis) venom is lethal to bedbugs. Rodents eat bedbugs, but bats do not, due to their distaste for the bedbug alarm pheromone, which is released when they are attacked. Biological control is not very practical for eliminating bedbugs from human dwellings.

Reproduction

All bedbugs mate via traumatic insemination.[1][20] Instead of inserting their genitalia into the female's reproductive tract as is typical in copulation, males instead pierce females with hypodermic genitalia and ejaculate into the body cavity.

The "bedbug alarm pheromone" consists of (E)-2-octenal and (E)-2-hexenal. It is released when a bedbug is disturbed, for example, during an attack by a predator. A 2009 study demonstrated that the alarm pheromone is also released by male bedbugs to repel other males who attempt to mate with them.

C. lectularius and C. hemipterus will mate with each other given the opportunity, but the eggs then produced are usually sterile. In a 1988 study, 1 egg out of 479 was fertile and resulted in a hybrid, C. hemipterus x lectularius.

Global resurgence

Bedbug cases have been on the rise across the world since the mid-1990s. Figures from one London borough show reported bedbug infestations doubling each year from 1995 to 2001. There is also evidence of a previous cycle of bedbug infestations in the U.K. in the mid-1980s. The U.S. National Pest Management Association reported a 71% increase in bedbug calls between 2000 and 2005. The Steritech Group, a pest-management company based in Charlotte, North Carolina, claimed that 25% of the 700 hotels they surveyed between 2002 and 2006 needed bedbug treatment. The resurgence led the United States Environmental Protection Agency to hold a National Bed Bug Summit in 2009.

The rise in infestations has been hard to track because bedbugs are not an easily identifiable problem. Most of the reports are collected from pest-control companies, local authorities, and hotel chains. Therefore, the problem may be more severe than is currently believed.

The cause of this resurgence is still uncertain, but it is thought to be related to increased international travel, the use of new pest-control methods that do not affect bedbugs, and increasing pesticide resistance.

One recent theory about bedbug reappearance involves potential geographic epicentres. Investigators have found three apparent United States epicentres at poultry facilities in Arkansas, Texas, and Delaware. It was determined that workers in these facilities were the main spreaders of these bedbugs, unknowingly carrying them to their places of residence and elsewhere after leaving work.

Bedbug pesticide-resistance appears to be increasing dramatically. Bedbug populations sampled across the U.S. showed several thousands of times greater resistant to pyrethroids than laboratory bedbugs. New York City bed bugs have been found to be 264 times more resistant to deltamethrin than Florida bedbugs due to nerve cell mutations. Another problem with current insecticide use is that the broad-spectrum insecticide sprays for cockroaches and ants that are no longer used had a collateral impact on bedbug infestations. Recently, a switch has been made to bait insecticides that have proven effective against cockroaches but have allowed bedbugs to escape the indirect treatment.

Bedbug pesticide-resistance appears to be increasing dramatically. Bedbug populations sampled across the U.S. showed several thousands of times greater resistant to pyrethroids than laboratory bedbugs. New York City bed bugs have been found to be 264 times more resistant to deltamethrin than Florida bedbugs due to nerve cell mutations. Another problem with current insecticide use is that the broad-spectrum insecticide sprays for cockroaches and ants that are no longer used had a collateral impact on bedbug infestations. Recently, a switch has been made to bait insecticides that have proven effective against cockroaches but have allowed bedbugs to escape the indirect treatment.

In 2003, Burl and Desiree Mathias, a brother and sister staying at a Motel 6 in Chicago were awarded $372,000 in punitive damages and $10,000 in actual damages after being bitten by bedbugs during their stay. These are only a few of the reported cases since the turn of the 21st century.

Once thought of as mainly afflicting the poor[citation needed], bedbug infestations have also affected the rich. Many of Manhattan's Upper East Side home owners have been afflicted, but they tend to be silent publicly in order not to ruin their property values and be seen as suffering a blight typically associated with the lower classes.

Life stages

Bedbugs will shed their skins through a molting process (ecdysis) throughout multiple stages of their lives. The discarded outer-shells look as clear, empty exoskeletons of the bugs themselves. Bedbugs must molt six times before becoming fertile adults.

Pesticide resistance

With the widespread use of DDT in the 1940s and '50s, bedbugs mostly disappeared from the developed world in the mid-twentieth century, though infestations remained common in many other parts of the world. Rebounding populations present a challenge because of developed resistance to various pesticides including DDT, and organophosphates. DDT was seen to make bedbugs more active in studies done in Africa.

Because some bed bug populations have developed a resistance to pyrethroid insecticides, there is growing interest in both synthetic pyrethroid and pyrrole insecticide chlorfenapyr; insect growth regulators such as hydroprene (Gentrol) are sometimes used.

Bites

Cimicosis is a skin condition caused by bedbug bites. Depending on individual sensitivity, bites can cause a raised red bump or flat welt, sometimes accompanied by very intense itching caused by an allergic reaction to the anesthetic in the bedbug's saliva. Reactions to bedbug bites may look like mosquito bites, though they tend to last longer. Bites may not be visible and can take up to nine days to appear.

Cimicosis is a skin condition caused by bedbug bites. Depending on individual sensitivity, bites can cause a raised red bump or flat welt, sometimes accompanied by very intense itching caused by an allergic reaction to the anesthetic in the bedbug's saliva. Reactions to bedbug bites may look like mosquito bites, though they tend to last longer. Bites may not be visible and can take up to nine days to appear.

Individual responses vary greatly. In about 50% of cases, there is no visible sign of bites, greatly increasing the difficulty of identifying and eradicating infestations. This means that itchy welts cannot be used as the only indicator, and that initial infestation can be asymptomatic and go undetected.

Serious bed bug infestations and chronic attacks can cause anxiety, stress, and insomnia. Development of refractory delusional parasitosis is possible, as victims develop an overwhelming obsession with bedbugs.

Patients given systemic corticosteroids and antihistamines for the itching associated with bites will still have visible signs of bites. Topical corticosteroids, such as hydrocortisone, can reduce lesions and decrease itching.

The application of hot water may relieve symptoms. The water temperature should be about 50 °C (120 °F), or this procedure may aggravate the symptoms. Disagreement exists as to why heat causes symptoms to abate. Heat might overwhelms the nerve endings that signal itch; it might neutralize the chemical causing inflammation, or it might trigger a large release of histamine, causing a temporary histamine deficit in the area. Another theory is that the heat denatures the proteins in the bedbug saliva, changing their composition enough so that they no longer trigger the body's defensive mechanisms.

Disease transmission

Bed bugs would seem to have all the prerequisites for passing diseases from one host to another, and at least twenty-seven known pathogens (some estimates are as high as forty-one) are capable of living inside a bed bug or on its mouthparts, yet there are no known cases of such transmission. Extensive laboratory testing indicates that bed bugs are unlikely to pass disease from one person to another.

Bed bugs would seem to have all the prerequisites for passing diseases from one host to another, and at least twenty-seven known pathogens (some estimates are as high as forty-one) are capable of living inside a bed bug or on its mouthparts, yet there are no known cases of such transmission. Extensive laboratory testing indicates that bed bugs are unlikely to pass disease from one person to another.

Other effects on health

The salivary fluid injected by bed bugs can cause skin to become irritated and inflamed, although individuals can differ in their sensitivity. A few cases of bullous eruptions have been reported Anaphylactoid reactions from the injection of serum and other nonspecific proteins are observed and the saliva of the bedbugs may cause anaphylactic shock, though rarely. In rare cases of intense and neglected infestation, sustained feeding by bedbugs may lead to anemia. Secondary bacterial infection (i.e., infections from scratching itchy skin too much) are possible. Systemic poisoning may occur if the bites are numerous.

History

Bedbugs were mentioned in ancient Greece as early as 400 BCE (later mentioned by Aristotle). Pliny's Natural History, first published c. 77 CE in Rome, claimed that bedbugs had medicinal value in treating ailments such as snake bites and ear infections. (Belief in the medicinal use of bedbugs persisted until at least the 18th century, when Guettard recommended their use in the treatment of hysteria.) Bedbugs were first mentioned in Germany in the 11th century, in France in the 13th century, and in England in 1583, though they remained rare in England until 1670. It was believed by some in the 18th century that bedbugs had been brought to London with supplies of wood to rebuild the city after the Great Fire of London (1666). Scopoli noted their presence in Carniola (present day Slovenia and Italy) in the 18th century.

Bedbugs were known at least as early as 1726 in Jamaica.

Eighteenth and 19th century Europeans believed bedbugs to feed on the sap of certain trees (especially fir), paste (which may have included tree sap), other insects, and Acari.

Prior to the mid-twentieth century, bedbugs were very common. According to a report by the UK Ministry of Health, in 1933 there were many areas where all the houses had some degree of bedbug infestation

Traditional control methods

Plants traditionally used as bedbug repellents include black cohosh (Actaea racemosa), Pseudarthna hookeri, and Laggera alata (Chinese yángmáo cÇŽo | 羊毛è‰), though information about their effectiveness is lacking. Eucalyptus saligna oil was reported by some Zairean researchers to kill bedbugs, among other insects.

In the 18th century, turpentine was used in combination with henna (Lawsonia inermis, aka camphire) flowers and alcohol, as an insecticide that also reputedly killed bedbug eggs.

Other items that were believed to kill bedbugs in the early 19th century include "infused oil of Melolontha vulgaris" (presumably a kind of cockchafer), fly agaric (Amanita muscaria), Actaea spp. (e.g. black cohosh), tobacco, "heated oil of Terebinthina" (i.e. turpentine), wild mint (Mentha arvensis), narrow-leaved pepperwort (Lepidium ruderale), Myrica spp. (e.g. bayberry), Robert Geranium (Geranium robertianum), bugbane (Cimicifuga spp.), "herb and seeds of Cannabis", "Opulus" berries (possibly a kind of maple, or European cranberrybush), masked hunter bugs (Reduvius personatus), "and many others." In the mid-19th century, smoke from peat fires was recommended.

Other items that were believed to kill bedbugs in the early 19th century include "infused oil of Melolontha vulgaris" (presumably a kind of cockchafer), fly agaric (Amanita muscaria), Actaea spp. (e.g. black cohosh), tobacco, "heated oil of Terebinthina" (i.e. turpentine), wild mint (Mentha arvensis), narrow-leaved pepperwort (Lepidium ruderale), Myrica spp. (e.g. bayberry), Robert Geranium (Geranium robertianum), bugbane (Cimicifuga spp.), "herb and seeds of Cannabis", "Opulus" berries (possibly a kind of maple, or European cranberrybush), masked hunter bugs (Reduvius personatus), "and many others." In the mid-19th century, smoke from peat fires was recommended.

The use of black pepper is attested in George Orwell's 1933 non-fiction book Down and Out in Paris and London.

Dusts have been used to ward off insects from grain storage for centuries, including "plant ash, lime, dolomite, certain types of soil, and diatomaceous earth (DE) or Kieselguhr"[52] Of these, Diatomaceous earth in particular has seen a revival as a non-toxic residual pesticide for bedbug abatement. When it attaches to a bedbug, it abrades the waxy cuticle that covers its exosekeleton, causing it to die of dehydration[citation needed]. Insects exposed to diatomaceous earth may, however, take several days to die.

Basket-work panels were put around beds and shaken out in the morning, in the UK and in France in the 19th century. Scattering leaves of plants with microscopic hooked hairs around a bed at night, then sweeping them up in the morning and burning them, was a technique reportedly used in Southern Rhodesia and in the Balkans.

Infestation Vectors

Among the way in which dwellings can become infested with bedbugs:

Among the way in which dwellings can become infested with bedbugs:

- from bugs and eggs that "hitchhiked in", on clothing and luggage;

- from infested items (e.g., furniture, clothes) brought in;

- from a nearby dwelling or infested item, if there are easy routes

- via wild animals (e.g. bats, birds) and pets can bring them in

Bedbugs can infest nursing homes, furniture rental stores, hospitals, jails, homeless shelters, movie theaters, cruise ships, public housing, moving vehicles, and public transportation.

Nesting locations

Bedbugs can be found on their own but often congregate once established. They usually remain close to hosts, commonly in or near beds or couches. Nesting locations can vary greatly, however, including luggage, vehicles, and bedside clutter. Bedbugs may also nest near animals that have nested within a dwelling, such as bats, rodents, or birds.

Detection

Bedbugs are elusive and usually nocturnal, which can make individual bugs difficult to detect. Bedbugs often lodge unnoticed in dark crevices, and eggs can be nestled in fabric seams.

Signs of bedbugs often appear before bugs are seen. These include fecal spots, crushed bedbugs and/or blood smears on sheets, moults, itchy welts from their bites (in those that react), etc.

Canine detection teams can pinpoint infestations. Bed bug detection dogs are trained to find the bed bugs through smell, often in a matter of minutes, where a (human) pest control practitioner might take an hour, and with an accuracy rate of 90%. In the United States, about 100 dogs are used to find bed bugs as of mid-2009.

Residence

Residence  Location

Location

A bedbug pierces the skin of its host with two hollow feeding tubes. With one tube it injects its saliva, which contains anticoagulants and anesthetics, while with the other it withdraws the blood of its host. After feeding for about five minutes, the bug returns to its hiding place.

A bedbug pierces the skin of its host with two hollow feeding tubes. With one tube it injects its saliva, which contains anticoagulants and anesthetics, while with the other it withdraws the blood of its host. After feeding for about five minutes, the bug returns to its hiding place. Bedbug pesticide-resistance appears to be increasing dramatically. Bedbug populations sampled across the U.S. showed several thousands of times greater resistant to pyrethroids than laboratory bedbugs. New York City bed bugs have been found to be 264 times more resistant to deltamethrin than Florida bedbugs due to nerve cell mutations. Another problem with current insecticide use is that the broad-spectrum insecticide sprays for cockroaches and ants that are no longer used had a collateral impact on bedbug infestations. Recently, a switch has been made to bait insecticides that have proven effective against cockroaches but have allowed bedbugs to escape the indirect treatment.

Bedbug pesticide-resistance appears to be increasing dramatically. Bedbug populations sampled across the U.S. showed several thousands of times greater resistant to pyrethroids than laboratory bedbugs. New York City bed bugs have been found to be 264 times more resistant to deltamethrin than Florida bedbugs due to nerve cell mutations. Another problem with current insecticide use is that the broad-spectrum insecticide sprays for cockroaches and ants that are no longer used had a collateral impact on bedbug infestations. Recently, a switch has been made to bait insecticides that have proven effective against cockroaches but have allowed bedbugs to escape the indirect treatment. Cimicosis is a skin condition caused by bedbug bites. Depending on individual sensitivity, bites can cause a raised red bump or flat welt, sometimes accompanied by very intense itching caused by an allergic reaction to the anesthetic in the bedbug's saliva. Reactions to bedbug bites may look like mosquito bites, though they tend to last longer. Bites may not be visible and can take up to nine days to appear.

Cimicosis is a skin condition caused by bedbug bites. Depending on individual sensitivity, bites can cause a raised red bump or flat welt, sometimes accompanied by very intense itching caused by an allergic reaction to the anesthetic in the bedbug's saliva. Reactions to bedbug bites may look like mosquito bites, though they tend to last longer. Bites may not be visible and can take up to nine days to appear. Bed bugs would seem to have all the prerequisites for passing diseases from one host to another, and at least twenty-seven known pathogens (some estimates are as high as forty-one) are capable of living inside a bed bug or on its mouthparts, yet there are no known cases of such transmission. Extensive laboratory testing indicates that bed bugs are unlikely to pass disease from one person to another.

Bed bugs would seem to have all the prerequisites for passing diseases from one host to another, and at least twenty-seven known pathogens (some estimates are as high as forty-one) are capable of living inside a bed bug or on its mouthparts, yet there are no known cases of such transmission. Extensive laboratory testing indicates that bed bugs are unlikely to pass disease from one person to another.

Other items that were believed to kill bedbugs in the early 19th century include "infused oil of Melolontha vulgaris" (presumably a kind of cockchafer), fly agaric (Amanita muscaria), Actaea spp. (e.g. black cohosh), tobacco, "heated oil of Terebinthina" (i.e. turpentine), wild mint (Mentha arvensis), narrow-leaved pepperwort (Lepidium ruderale), Myrica spp. (e.g. bayberry), Robert Geranium (Geranium robertianum), bugbane (Cimicifuga spp.), "herb and seeds of Cannabis", "Opulus" berries (possibly a kind of maple, or European cranberrybush), masked hunter bugs (Reduvius personatus), "and many others." In the mid-19th century, smoke from peat fires was recommended.

Other items that were believed to kill bedbugs in the early 19th century include "infused oil of Melolontha vulgaris" (presumably a kind of cockchafer), fly agaric (Amanita muscaria), Actaea spp. (e.g. black cohosh), tobacco, "heated oil of Terebinthina" (i.e. turpentine), wild mint (Mentha arvensis), narrow-leaved pepperwort (Lepidium ruderale), Myrica spp. (e.g. bayberry), Robert Geranium (Geranium robertianum), bugbane (Cimicifuga spp.), "herb and seeds of Cannabis", "Opulus" berries (possibly a kind of maple, or European cranberrybush), masked hunter bugs (Reduvius personatus), "and many others." In the mid-19th century, smoke from peat fires was recommended. Among the way in which dwellings can become infested with bedbugs:

Among the way in which dwellings can become infested with bedbugs: