Dyker Heights is a residential neighborhood in the southwest corner of the Borough of Brooklyn in New York City, USA. It is sandwiched among Bay Ridge, Bensonhurst, and Gravesend Bay. According to the Post Office, Dyker Heights is bounded to the west by Interstate 278, to the north by Bay Ridge Avenue, to the east by Fourteenth Avenue, and to the south by Fort Hamilton. The Dyker Beach Golf Course extends to the Belt Parkway. Dyker Heights originated as a speculative luxury housing development in October 1895 when Walter Loveridge Johnson developed a portion of woodland into a suburban community. During the height of his development, the boundaries were primarily between Tenth Avenue and Thirteenth Avenue and from 79th Street to 86th Street. The finest homes of the development were situated along the top of the 110-foot (34 m) hill, at about Eleventh Avenue and 82nd Street. Dyker Heights is patrolled by the 68th Precinct of the NYPD.[2]

History

New Utrecht Woodlands

The neighborhood of Dyker Heights lies within the boundaries of the original Dutch town of New Utrecht settled in 1657. The area that is now as Dyker Heights was not developed in the 17th or 18th centuries because the land was too sloped for farming. It remained common woodland until the mid-19th century. The trees of this forest were used by the townsfolk as a source of firewood and construction material. When the agricultural industry of New Utrecht changed from the farming of grains to the cultivation of market garden produce, the trees were cleared and the area became a large market garden with tomatoes, cabbages, and potatoes, among other produce.[3]

De Russy’s Estate

The first house built at the top of the hill (what is now Eleventh Avenue and Eighty-Second Street, at about 110 feet (34 m) above sea level) was built in the late 1820s by Brigadier General René Edward De Russy of the United States Army. De Russy was a military engineer who built many forts in the United States – from the Canadian border and the eastern seaboard to the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific coast – including Fort Hamilton in Brooklyn.[4] Since this is the tallest natural point in southwest Brooklyn, De Russy built his homestead here – it afforded a clear view of the harbor and its defenses, especially Fort Hamilton which was complete by November 1831. De Russy died in 1865 and his wife, Helen, sold the property in 1888 to Jane Elisabeth Loveridge and Frederick Henry Johnson.

Frederick H. Johnson’s speculation

According to the Brooklyn Eagle, Frederick Johnson did “much toward developing the locality in which he resided. He was the author of the original New Utrecht Improvement Bill, and an ardent advocate of the annexation of the Town to this City.”[5] The Town of New Utrecht was annexed to the City of Brooklyn on July 1, 1894. On January 1, 1898, the City of Brooklyn was annexed to the City of New York. Involved with real estate, Johnson was probably very aware of the real estate pressures on and potential of the real estate in New Utrecht. With this in mind, he most likely purchased the De Russy Estate with the intention of building an upscale residential neighborhood similar to Bensonhurst-by-the-Sea, built by James D. Lynch from 1880-1890 in the Bath Beach section of New Utrecht.[6] At that time, The Real Estate Record claimed Bensonhurst-by-the-Sea was “the most perfectly developed suburb ever laid out around New York.”[7] The restrictions placed upon the property made Bensonhurst-by-the-Sea “a model settlement, where some of the most refined, intelligent and cultured of New York and Brooklyn’s citizens have built their homes.”[7]

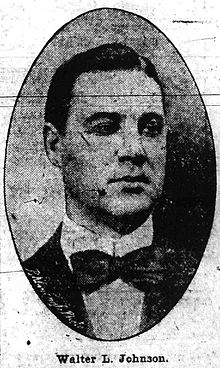

Walter L. Johnson’s vision

Following Frederick Johnson’s death on August 15, 1893 at the age of 52, his second son, Walter Loveridge Johnson, took over the real estate business and by October 1895 Walter started Dyker Heights on his parents’ property. Walter L. Johnson named his development “Dyker Heights” after the Dyker Meadow and Beach, which his development overlooks. The meadow and beach received their name from either the Van Dykes (an original New Utrecht family) who built the dykes to drain the meadow, or for the dykes that the Van Dykes built.[6]

Walter L. Johnson was able to develop this portion of New Utrecht woodland into a residential community by making necessary improvements to it. In 1890, the only roads present were Kings Highway, Eighty-Sixth Street, Denyse’s Lane, and a small unnamed road near Tenth Avenue – none of which were paved and only Eighty-Sixth Street was a thoroughfare specifically planned as such. The remaining land was unimproved. Johnson continued Brooklyn’s street grid south with macadam pavement, graded the properties, installed gas, water, telephone, and electricity lines, and planted sugar maple trees – seven on the avenues and twenty along the streets. This opened over two hundred more building sites between Tenth and Thirteenth avenues as well as between Seventy-Ninth Street and Eighty-Sixth Street.

The original three

In 1895, Johnson, very much aware of the successful Bensonhurst-by-the-Sea, built three homes. His home was on the southwest corner of Eleventh Avenue and Eighty-Second Street (across the Avenue from the home of his mother), Albert Edward Parfitt’s home was on Eighty-Second Street next to Johnson’s, and the last, closest to Tenth Avenue, was the home of Arthur S. Tuttle who was Assistant Engineer of The Water Supply of The City Works Department of The City of Brooklyn. Parfitt was the architect of these three homes. Johnson’s house burned down before 1900, Parfitt’s was demolished by a developer in 1928 and replaced with seven, run-of-the-mill, fully detached, single-family homes, and Tuttle’s house was remodeled over 10 years ago and clad in bright-white and sky-blue brick.[6]

The praise from the print press

“The Handsomest Suburb in Greater New York”

Throughout the infancy of the development, Walter L. Johnson was able to use the print press to his advantage. He advertised his suburban homes heavily and stated that the high ground, magnificent ocean view, and careful restrictions made Dyker Heights the handsomest suburb in Greater New York. Based on the newspaper accounts, he was right. In 1896 Johnson built and sold thirty homes in Dyker Heights. By January 1897, the Brooklyn Eagle reported on his achievements. “Mr. Johnson has met with great success in the development of Dyker Heights and had probably done more business and made more sales during the past year than all the rest of the surrounding settlements combined.”[8] In April 1898 sales were still very strong. “Dyker Heights still holds its lead among the suburban sections in building operations, over forty houses having been erected there during the past year… and there are fully twenty more houses about to be built.”[9] One of its many advantages was the location, which according to the Brooklyn Eagle, “is one of the finest in Greater New York, commanding an extensive view of water from Sandy Hook to the New Jersey Palisades, with Staten Island and the shores of New Jersey directly in front.”[10] Still more praise in February 1899, “Dyker Heights has been one of the most successful and the most rapid in growth of any of the suburban settlements, over one hundred dwellings, costing from $5,000 to $25,000 each, having been erected there within the last two years.”[11]

“An ideal spot for a home”

In September 1899, the Wall Street Journal even reported on the advantages of the development, recommending it to “the busy man of Wall Street” because of “its magnificent transportation facilities… it can be reached via the Thirty-Ninth Street Brooklyn Ferry and Eighty-Sixth Street Nassau Line in 45 minutes.”[12] In addition the article claimed that “the 45 minutes’ trip between Dyker Heights and Wall Street by water and rail is as invigorating as the Dyker Heights climate is healthy-living. The rare opportunities afforded by Dyker Heights to the wealthy and to those in moderate circumstances are due largely to the energy, enterprise and good taste of its founder, Mr. Walter L. Johnson.”[12] A month later, the Wall Street Journal published “An Ideal Spot for a Home.” From that article, one can clearly see why Dyker Heights was so successful. Its location and luxurious homes were first rate, “[Dyker Heights] is without a rival as to location, situated as it is at an elevation of [110] feet above the sea level, and is directly opposite the new Dyker Meadow Park… which will be the only seaside park in Greater New York.”[13] The article also explained the exclusiveness of the property, which can be seen in “its massive stone piers with heavy wrought-iron lamps and scrolls” that adorn the entrances.[13] In December 1899 the Brooklyn Eagle reported that, “work has recently been commenced upon thirty high class Houses, the demand for which runs a dead heat with the supply.”[14]

“One of the most magnificent”

Johnson set very high standards for the community: the Wall Street Journal explained “the property is carefully restricted against all nuisances and no building can be erected upon a plot of less than 60 feet (18 m) in width by 100 feet (30 m) in depth, and each building must cost at least $4,000 and stand well back from the street.”[13] These regulations, which were similar to those of Bensonhurst-by-the-Sea, were active until 1915. However, the most desirable feature of the area was still the “uninterrupted view of the lower bay from The Narrows to Sandy Hook and Atlantic Ocean, [which] is one of the most magnificent in the country, and nowhere else in the consolidated city is there anything to compare it with. From here can be seen a marine panorama hard to beat.”[13] Dyker Heights was so desirous that important members of society flocked to it. The Brooklyn Eagle reported in December 1899 that this “drain” on the more established social neighborhoods such as Brooklyn Heights and those in Manhattan, “almost threatens to lower the social tone of the neighborhoods where this universal exodus is effecting a gradual change in the character of the population.”[14]

First public kindergarten for the blind

Property on Eighty-fourth Street near Thirteenth Avenue was made available to the International Sunshine Society in 1906 by lawyer, financier, and promoter George E. Crater, Jr.[15] The society was able to acquire the house for $11,000, roughly half the market value, and opened the Dyker Heights Home for Blind Babies on 1 November 1906. Cynthia W. Alden, Mary C. Seward, and other society officers worked with the New York City Board of Education to establish the first public kindergarten for blind children at the home in 1907.[16] The original building is gone, but the work begun in Dyker Heights provided a legacy of significant reforms in the public education of blind children within New York and other regions of the United States.

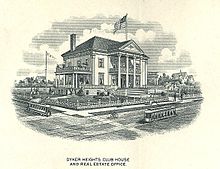

The club house and real estate office

One of the many focal points of the neighborhood was the Dyker Heights Club, which started in October 1896.[6] By spring of 1898 the Club had a $30,000 club house designed by Albert Edward Parfitt on an $8,500 lot, measuring 200 × 200, located on the northeast corner of Thirteenth Avenue and Eighty-Sixth Street. Johnson moved his real estate office into the club house and hired a full-time architect, Constantine Schubert, who was also a Dyker Heights homeowner. This grand, neo-classical building was sadly demolished in 1929 by the Archbishop John Hughes Knights of Columbus Club, when they acquired the property for $60,000.[17]

Early in the history of Dyker Heights, Walter L. Johnson continually purchased consecutive tracts of land until the boundaries of Dyker Heights stretched from Seventy-Ninth Street in the north, roughly Eighty-Sixth Street in the south, Tenth Avenue to the west, and about 300 feet (90 m) east of Thirteenth Avenue to the east. However, the boundaries of the Neighborhood of Dyker Heights are now defined by the Dyker Heights Post Office on the northwest corner of 13th and 84th Streets; along its northeast edge runs Bay Ridge Avenue; Sixteenth Avenue is its southeast boundary; Fort Hamilton makes its southwest border; and Interstate 278 is the northwest limit.

Homes in Dyker Heights

Original homes

In December 1899, the Brooklyn Eagle wrote a very detailed description of the homes in Dyker Heights:

“The typical Dyker Heights residences have five rooms each on the first and second floors and four rooms on the third. Upon entrance, the inmate or visitor is ushered into a hall twelve feet wide which runs back to the butler’s pantry. To the right of this hall is the parlor and library and to the left the reception and dining rooms. The rear space is taken up by the kitchen, butler’s pantry and washrooms with tiled floors. Birdseye maple is used in the finishing of the parlor and quartered oak in that of the library, one with mantles of the same wood in fancy tile finish. A large fireplace with ornamental andirons completes the mural decoration. The ceilings are ten feet high on the first floor, while nine feet is the elevation of the second and eight feet that of the third floor. Usually the dining room is fifteen feet square and finished off in quartered sycamore. Like the hall, the reception room is done off in quartered oak, but is circular in form and has a diameter of ten feet. In the kitchen is a glazed fireplace, while below stairs, speaking from a first floor level, are the cellar and laundry, with a depth of eight feet, and an asphalt double concrete floor.”[14]

“Of the five rooms on the second floor, one is a sitting room and the remainder sleeping apartments, all of which are finished in quartered oak and sycamore. A large bathroom with tiled floors takes up the remaining space of the second story. Rising to the third floor we find plain cypress as the invariable finish of the apartments, which comprise two servants’ rooms, a card or sitting room and a billiard parlor wainscoted on the sides and provided with seats for the players and onlookers. It may be noted further that the reception room and dining room are also wainscoted six feet high.”[14]

Of the approximately 150 homes initially built by Walter L. Johnson, about half remain; while the others have been razed and replaced by large Mediterranean villas, condos, as well as semi and fully attached homes. Very few of the newer homes fit into the historic context of Dyker Heights, and many of the original surviving homes have been extensively renovated and remodeled.[18]

Bath Beach Bay Ridge Bensonhurst Borough Park Dyker Heights Fort Hamilton New Utrecht