Coney Island is a peninsula and beach on the Atlantic Ocean in southern Brooklyn, New York, United States. The site was formerly an outer barrier island, but became partially connected to the mainland by landfill.

Coney Island is possibly best known as the site of amusement parks and a major resort that reached their peak during the first half of the 20th century. It declined in popularity after World War II and endured years of neglect. In recent years, the area has seen the opening of MCU Park and has become home to the minor league baseball team the Brooklyn Cyclones.

The neighborhood of the same name is a community of 60,000 people in the western part of the peninsula, with Sea Gate to its west, Brighton Beach and Manhattan Beach to its east, and Gravesend to the north.

Geography

Coney Island is the westernmost part of the barrier islands of Long Island, about 4 miles (6.4 km) long and 0.5 miles (0.80 km) wide. Formerly it was an island, separated from the main part of Brooklyn by Coney Island Creek, which was partially tidal mudflats, but it has since been developed into a peninsula. There were plans early in the 20th century to dredge and straighten the creek as a ship canal, but they were abandoned, and the center of the creek was filled in for construction of the Belt Parkway before World War II. The western and eastern ends are now peninsulas.

History

Etymology

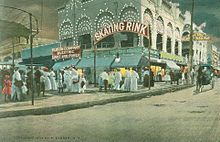

Coney Island, c. 1914, by Edward Henry Potthast

The Native American inhabitants of the region, the Lenape, called the island Narrioch—meaning “land without shadows”—because, as with other south shore Long Island beaches, its orientation means the beach remains in sunlight all day.[citation needed]

![]()

Following European settlement, New York State and New York City were originally a Dutch colony and settlement, named Nieuw Nederland and Nieuw Amsterdam. The Dutch name for the island—originally Conyne Eylandt, or Konijneneiland in modern Dutch spelling[2]—probably precedes the similar English name, Coney Island, with both translating as “Rabbit Island”.[3] As on other Long Island barrier islands, Coney Island had many and diverse rabbits, and rabbit hunting prospered until resort development eliminated their habitat. The Dutch name is found on the New Netherland map of 1639 by Johannes Vingboon, which is before any known English records.[4]

Coney Island therefore appears to be the English adaptation of the Dutch name. The word “coney” was popular in English at the time as an alternative for rabbit; while coney survives in archaic and dialectal contexts, a later adaptation, “bunny”, is now in common use. Coney came into the English language through the Old French word conil, which itself derived from the Latin word for rabbit, cuniculus. The English name “Conney Isle” appeared on maps as early as 1690,[5] and by 1733 the modern name, Coney Island, was used.[6] Joseph DesBarre’s chart of New York harbor in the 1779 work Atlantic Neptune,[7] and John Eddy’s map of 1811, both use the modern spelling.[8]

Although the history of Coney Island’s name and its anglicization can be traced through historical maps spanning the 17th century to the present,[9] and all the names translate to Rabbit Island in modern English, there are still those who contend that the name derives from other sources.[who?] Also possible is the Irish Gaelic name for Rabbit which is Coinín, which is also anglicised to Coney. Ireland has many islands named Coney Island, all of which predate this one. Some claim that an Irish captain named Peter O’Connor named Coney Island in the 18th century, after an island in County Sligo known as both Coney Island and Inishmulclohy. Another purported origin is from the name of the Indian tribe, the Konoh, who supposedly once inhabited it. A further claim is that the island is named after Henry Hudson’s right-hand-man, John Coleman, supposed to have been slain by Indians.[10]

Resort

See also: Luna Park, Coney Island , Dreamland (amusement park) , and Steeplechase Park

Due to Coney Island’s location—easily reached from Manhattan and other boroughs of New York City, yet distant enough to suggest a proper vacation—it began attracting holidaymakers in the 1830s and 1840s, when carriage roads and steamship services reduced travel time from a half-day journey to just two hours.[11]

The original Coney Island Hotel was constructed in 1829, with The Brighton Hotel, Manhattan Beach Hotel, and Oriental Hotel opening soon after, with each trying to provide an increasing level of elegance. Coney Island became a major resort destination after the American Civil War, as excursion railroads and the Coney Island & Brooklyn Railroad streetcar line reached the area in the 1860s, and the Iron steamboat company arrived in 1881. The two Iron Piers served as docks for the steamboats until they were destroyed in the 1911 Dreamland fire.

When the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company electrified the steam railroads and connected Brooklyn to Manhattan via the Brooklyn Bridge at the beginning of the 20th century, Coney Island soon turned from a resort to a location accessible to day-trippers from New York City, especially those escaping the summer heat.[citation needed]

Charles I. D. Looff, a Danish woodcarver, built the first carousel at Coney Island in 1876. It was installed at Vandeveer’s bath-house complex at West 6th Street and Surf Avenue, which later became known as Balmer’s Pavilion. The carousel consisted of hand-carved horses and animals standing two abreast, with a drummer and a flute player providing the music. A tent-top provided protection from the weather. The fare was five cents.[citation needed]

From 1885 to 1896, the Coney Island Elephant was the first sight to greet immigrants arriving in New York, who would see it before the Statue of Liberty became visible.

In 1915 the Sea Beach Line was upgraded to a subway line. This was followed by upgrades to the other former excursion roads, and the opening of the New West End Terminal in 1919, thus ushering in Coney Island’s busiest era.[12]

Nathan’s Famous original hot dog stand opened on Coney Island in 1916 and quickly became a landmark. An annual Nathan’s Hot Dog Eating Contest has been held there annually on July 4 since its opening, but has only attracted broad attention and television coverage since the late 1990s.[citation needed]

After World War II, contraction began seriously from a number of pressures. Air conditioning in movie theaters and then in homes, along with the advent of automobiles which provided access to the less crowded and more appealing Long Island state parks, especially Jones Beach State Park, lessened the attractions of Coney’s beaches. Luna Park closed in 1946 after a series of fires, and the New York street gang problems of the 1950s spilled into Coney Island. The presence of threatening youths did not impact the beach-goers, but discouraged visitors to the rides and concessions which were staples of the Coney Island economy. The local economy was dealt a severe blow by the 1964 closing of Steeplechase Park, the last of the major amusement parks.[citation needed]

Development

Main article: Coney Island Development

Development on Coney Island has always been controversial. When the first structures were built around the 1840s, there was an outcry to prevent any development on the island and preserve it as a natural park. Starting in the early 20th century, the City of New York made efforts to condemn all buildings and piers built south of Surf Avenue, with the local amusement community opposing the city. Eventually a settlement was reached where the beach was declared as not beginning until 1,000 ft (300 m) south of Surf Avenue, the territory marked by a city-owned boardwalk, while the city would demolish any structures that had been built over public streets in order to reclaim beach access.[citation needed]

In 1944, Robert Moses actively opposed the “tawdry” entertainment at Coney Island and discouraged the building of new amusements. By 1949, Moses moved the boardwalk back from the beach several yards, demolishing many structures, including the city’s municipal bath house. He would later demolish several blocks of amusements to clear land for both the New York Aquarium, where Dreamland once stood, and the Abe Stark Ice Skating Rink. In 1953, Moses had the entire island rezoned for residential use only, and announced plans to demolish the amusements to make room for low income housing. After public complaints, the Estimate Board reinstated some areas as protected for amusement use only, leading to many public land battles.[citation needed]

In 1964, Coney Island’s last remaining large theme park, Steeplechase Park, closed and the property was sold to developer Fred Trump. Trump wanted to build luxury apartments on the old Steeplechase property and spent ten years battling in court to get the property rezoned. After a decade of court battles, Trump exhausted his legal options and the property remained zoned for amusements. He eventually leased the property to Norman Kaufman, who ran a small collection of fairground amusements on a corner of the site, calling his amusement park Steeplechase Park.[citation needed] However, between the loss of both Luna Park and the original Steeplechase Park, as well as an urban-renewal plan that took place in the surrounding neighborhood, involving middle class houses being replaced with low income housing projects, fewer visitors came to Coney Island. In the late 1970s the city proposed a plan to revitalize Coney Island by bringing in gambling casinos, as had been done in Atlantic City, but gambling was never legalized for Coney Island, and the area ended up with vacant lots.[citation needed]

In 1994 Rudy Giuliani took office as mayor of New York, and supported a plan to build a sporting complex named Sportsplex, provided it include a stadium for a minor league baseball team owned by the New York Mets. Once the stadium was completed Giuliani reneged on the Sportsplex deal, and The Mets decided to call the minor league team the Brooklyn Cyclones and sold the naming rights to the stadium to Keyspan Energy. Executives from Keyspan complained that the stadium’s line of view from the rest of the Coney Island amusement area was blocked by the derelict Thunderbolt roller-coaster, and the following month Giuliani ordered an early-morning bulldozing of the Thunderbolt.[citation needed]

In 2003, Mayor Michael Bloomberg took an interest in revitalizing Coney Island as a possible site for the 2012 Olympics. When the city lost the bid for the Olympics, revitalization plans were rolled over to the Coney Island Development Corporation (CIDC), which came up with a plan to restore the resort. Shortly before the CIDC’s plans were released, a development company, Thor Equities, purchased all of Bullard’s western property, sold it to Taconic Investment Partners, and used much of the proceeds to purchase or offer to purchase every piece of property inside the traditional amusement area. In September 2005, Thor went public with a plans to build a large Bellagio-style hotel resort surrounded by rides and amusements. Plans of the hotel showed it covering the entire amusement area from the Aquarium to beyond MCU Park, and requiring the demolition of The Wonder Wheel, Cyclone, and Nathan’s original hot dog stand, as well as the new MCU Park.[citation needed]

Late in 2006 Thor purchased Coney Island’s last remaining amusement park, Astroland, and announced plans to close it after the 2007 season and build a Nickelodeon-themed hotel on the site. In January 2007 Thor released plans for a new amusement park to be built on the Astroland site called Coney Island Park.[13] In late 2007 Thor began to evict businesses from the buildings it owned along the boardwalk, but when one of the business owners complained, Thor reinstated their leases.[citation needed]

In early 2007, the Municipal Art Society launched the initiative ImagineConey,[14] as discussion of a rezoning plan that highly favored housing and hotels began circulating from the Department of City Planning.[15] City Planning certified the rezoning plan in January 2009. As of 2010 the plan was going through the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP) process,[16] with Thor Equities saying it hoped to complete the project by 2011.[17] The Coney Island Aquarium was also planning a renovation from the mid-2000s.[18] In June 2009, the city’s planning commission unanimously approved the construction of 4,500 units of housing and 900 affordable units, and vowed to “preserve, in perpetuity, the open amusement area rides that everyone knows and loves”, while protesters argued that the “20 percent affordable-housing component is unreasonably low.”[19]

Demographics

As of the 2000 census, there were 51,205 people living in Coney Island. Of those people, 29.3% were Black or African American, 51.2% were White, 18% were Hispanic or Latino, 3.8% were Asian, 0.5% were Native American, 0.1% were Pacific Islander, 7.6% were some other race, and 3.7% described themselves as two or more races. 70.5% had a high school degree or higher, and 20.7% had a bachelor’s degree or higher. The median household income as of 1999 was $21,281.

Communities

The neighborhoods on Coney Island, from west to east, are Sea Gate, Coney Island proper, Brighton Beach, and Manhattan Beach. Sea Gate is a private community, one of only a handful of neighborhoods in New York City where the streets are owned by the residents and not the city; Sea Gate and the Breezy Point Cooperative are the only city neighborhoods cordoned off by a fence and gate houses.

The majority of Coney Island’s population resides in approximately thirty 18- to 24-storey towers, mostly various forms of public housing. In between the towers are many blocks that were filled with vacant and burned out buildings. Since the 1990s there has been steady revitalization of the area. Many townhouses were built on empty lots, popular franchises opened, and Keyspan Park was built to serve as the home for the Brooklyn Cyclones baseball team. Once home to many Jewish residents, Coney Island’s main population groups today are African American, Italian American, Hispanic, and recent Russian and Ukrainian immigrants.

Brighton Beach, also known as “LittleOdessa” Chinatown Coney Island Gerritsen Beach Gravesend Homecrest Manhattan Beach Mapleton, Grays Farm Midwood Sea Gate Sheepshead Bay