This article includes a subtopic, Gilded Age. For related topical usage, see Gilded age

Gravesend (pronounced GRAVE’S end, not grave SEND) is a neighborhood in the south-central section of the New York City borough of Brooklyn, USA.

The derivation of the name is unclear. Some speculate that it was named after the English seaport of Gravesend, Kent.[1] An alternative explanation suggests that it was named by Willem Kieft for the Dutch settlement of “‘s- Gravesande”, which means “Count’s Beach” or “Count’s Sand”.[2] There is also a town in the Netherlands called ‘s-Gravenzande.

Gravesend was one of the original towns in the Dutch colony of New Netherland and became one of the six original towns of Kings County in colonial New York. It was the only English chartered town in what became Kings County and was designated the “Shire Town” when the English assumed control, as it was the only one where records could be kept in English. Courts were removed to Flatbush in 1685. The former name survives, and is now associated with a neighborhood in Brooklyn. Gravesend is notable for being founded by a woman, Lady Deborah Moody; a land patent was granted to the English settlers by Governor Willem Kieft, December 19, 1645. A prominent early settler was Anthony Janszoon van Salee.

Gravesend Town encompassed 7,000 acres (28 km²) in southern Kings County, including the entire island of Coney Island, which was originally the town’s common lands on the Atlantic Ocean, divided up, as was the town itself, into 41 parcels for the original patentees. When the town was first laid out, almost half were salt marsh wetlands and sandhill dunes along the shore of Gravesend Bay.

As of 2007, Gravesend had a population of 181,651.[3]

Geography

The modern neighborhood of Gravesend lies between Coney Island Avenue to the east, Stillwell Avenue to the west, Kings Highway to the north, and Coney Island Creek and Shore Parkway to the south. To the east of Gravesend is Sheepshead Bay, to the northeast Midwood, to the northwest Bensonhurst, and to the west Bath Beach. To the south, across Coney Island Creek, lies the neighborhood of Coney Island, and across Shore Parkway lies Brighton Beach. The neighborhood center is still the four blocks bounded by Village Road South, Village Road East, Village Road North, and Van Sicklen Street, where the Moody House and Van Sicklen family cemetery are located. Next to, and parallel with the van Sicklen Family Cemetery is the Old Gravesend Cemetery, where Lady Moody is purported to be interred. (Gravesend Cemetery’s most exotic occupant is Egyptian émigré Mohammad Ben Misoud, who was part of a Coney Island attraction and was afforded a proper Muslim funeral upon his death in August, 1896.)

Gravesend is served by three lines of the New York City Subway system: the D elevated line (also called the BMT West End Line), at the 25th Avenue and Bay 50th Street stations; the F elevated line (also called the IND Culver Line), at the Kings Highway, Avenue U, and Avenue X stations, and the N open-cut line, (also called the BMT Sea Beach Line), at the Kings Highway, Avenue U, and Gravesend/86th Street stations. Gravesend is patrolled by the NYPD’s 60, 61, and 62 Precincts.[4]

History

Early history

The first known European to set foot in the area that would become Gravesend was Henry Hudson, whose ship, the Half Moon, landed on Coney Island in the fall of 1609.[dubious – discuss] The island and its environs were at that time inhabited by bands of Lenape people.

The land subsequently became part of the New Netherland Colony, and in 1643 it was granted to Lady Deborah Moody, an English expatriate who hoped to establish a community where she and her followers could practice their Anabaptist beliefs free from persecution. Due to clashes with the local native tribes the town wasn’t completed until 1645. But when the town charter was finally signed and granted it became one of the first such titles to ever be awarded to a woman in the new world.[5]

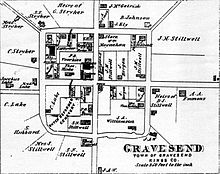

The town Lady Moody established was one of the earliest planned communities in America. It consisted of a perfect square surrounded by a 20-foot-high wooden palisade. The town was bisected by two main roads, Gravesend Road (now McDonald Avenue) running from north to south, and Gravesend Neck Road,[5] running from east to west (Map). These roads divided the town into four quadrants which were subdivided into ten plots of land each (The grid of the original town can still be seen on maps and aerial photographs of the area). At the center of town, where the two main roads met, a town hall was constructed where town meetings were held once a month.

The religious freedom of early Gravesend made it a desirable home for ostracized or controversial groups, such as the Quakers, who briefly made their home in the town before being chased out by New Netherland director general Petrus Stuyvesant, who was wary of Gravesend’s open acceptance of “heretical” sects.

In 1654 the people of Gravesend purchased Coney Island from the local natives for about $15 worth of seashells, guns, and gunpowder.

In August of 1776 Gravesend Bay was the landing site of thousands of British soldiers and German mercenaries from their staging area on Staten Island, leading to the Battle of Long Island (also Battle of Brooklyn). The troops met little resistance from the Continental Army advance troops under General George Washington then headquartered in New York City (at the time limited to the very tip of Manhattan Island). The battle would prove to be the largest fought in the entire war.[citation needed]

Gilded Age

Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries Gravesend remained a sleepy Long Island suburb. Then, with the opening of three prominent racetracks (Sheepshead Bay Race Track, Gravesend Race Track, and Brighton Beach Race Course) in the late 19th century, and the blossoming of Coney Island into a popular vacation spot, the town was transformed into a (relatively) bustling resort community.

The man who spearheaded this metamorphosis was John Y. McKane, a Sheepshead Bay carpenter and contractor who rose to become the Gravesend town supervisor, chief of police, chief of detectives, fire commissioner, schools commissioner, public lands commissioner, superintendent of the Sheepshead Bay Methodist Church, head tenor of the church choir, and, last but not least, Santa Claus at the annual Sabbath school Christmas celebration.

From the 1870s to the 1890s McKane cultivated Coney Island (which at that time was part of the township of Gravesend) as a pleasure ground, building much of it up, literally, with his own hands. As town constable he expanded the Gravesend police force considerably and could often be found patrolling the beaches himself armed with a pistol and an oversized billy club, (neither of which he was shy about using). But despite his honest beginnings, McKane quickly morphed into a corrupt Tammany Hall -style politician in the tradition of Boss Tweed. He used the pretense of town permits to extort tribute from every business, large and small, on Coney Island, and while he presented himself publicly as a champion of law and order, privately he was profiting mightily from the many brothels and gambling parlors that thrived in his bailiwick. It was during McKane’s reign that Coney Island came to be known by many as “Sodom by the Sea.”

McKane also rigged the political machine in Gravesend by stuffing the town voter registries with as many names as he could scrape up. Seasonal migrant workers, criminals, even the corpses in the town cemetery were eligible to vote in McKane’s Gravesend. And vote they all did, according to McKane’s will. Finally, on the eve of the 1893 election, William Gaynor, a lawyer running for Brooklyn Supreme Court Justice, decided to put McKane’s feet to the fire. As he was entitled to do by law, Gaynor dispatched over 20 Republican observers to examine the Gravesend voter registries and oversee the voting in all six districts of the town. But when the observers reached Gravesend town hall at dawn on election day, McKane, along with a large group of policemen and cronies, confronted them. When the observers balked and produced injunctions from the Brooklyn Supreme Court McKane supposedly declared “injunctions don’t go here” and ordered the men away. A scuffle ensued and five of the observers were beaten and arrested. To Mckane it was just another election day dust-up, but to the rest of the nation it was seen as an outrage (some even comparing it to an act of civil war). Early the following year McKane was brought to justice and sentenced to six years hard labor in Sing Sing prison. He was released near the end of the century and died of a stroke in his Sheepshead Bay home in 1899.

The removal of McKane paved the way for Gravesend and Coney Island to become part of the city of Brooklyn, which they did in 1894. It also allowed one of McKane’s most hated enemies, George C. Tilyou, to create one of Coney Island’s first amusement parks, Steeplechase Park, the opening of which ushered in Coney Island’s golden age.

Later years

Although Coney Island continued to be a major tourist attraction throughout the 20th century, the closing of Gravesend’s great racetracks in the century’s first decade caused the rest of the old town to recede back into obscurity. Most of it became a non-descript working class residential Brooklyn neighborhood. In the 1950s the city constructed the 28 building Marlboro Houses, located between Avenues V and X from Stillwell Avenue to the Gravesend Rail Yards. It is run by the New York City Housing Authority.[6] There is also crime around McDonald Avenue, under the elevated F Line, in the Southern part of Gravesend. The southern area of the Neighborhood has seen an increase in crime in its later years.[7] In 2009, the neighborhood saw 10 murders, putting it above national average.[8] The neighborhood matched its 2009 murder total, with 10 in 2010.[9] Beginning in the 1990s, with an influx of Sephardic Jews, the northeast section of the neighborhood saw the development of upscale single-family homes at prices upwards of $1 Million.[10]

Ethnic makeup

Gravesend’s earliest non-native settlers were predominantly English and Dutch. While slavery was legal in New York, the town also had a significant African American population, many of whom remained in the area even with the abolition of slavery. The now-defunct Gravesend Race Track opened on August 26, 1886 and hired mainly black workers who ended up moving into nearby homes. Later, there was a surge in Irish, Italian, and Jewish residents. Russian, Ukrainian, Chinese, Puerto Rican, and Mexican immigrants are the most recent residents to share the neighborhood. In 2008, The New York Times reported that the neighborhood had become particularly popular among Sephardic Jews.[10]

Facts

- Playwright Arthur Miller grew up in a modest house not far from Washington Cemetery in Gravesend. Mob Boss Carlo Gambino also lived much of his life in Gravesend.

- In the late 19th century Gravesend served as a testing ground for the Boynton Bicycle Railroad, the earliest forerunner of the monorail. The BBR consisted of a single-wheeled engine that hauled two double-decker passenger cars along a single track (a second rail above the train, supported by wooden arches, kept it from tipping over). The engine and cars were only four feet wide and were capable of speeds far greater than standard (and much bulkier) trains. In 1889 the BBR began running a short route between the Gravesend Station stop of the Sea Beach Railroad (near the intersection of 86th and west seventh streets) and Brighton Beach in Coney Island, a distance of just over a mile. Despite the smooth and speedy ride the BBR offered riders, it ultimately failed and the test route fell into disuse, along with the Boynton train itself and the shed that was built to house it.

- The bank robbery that inspired the movie Dog Day Afternoon happened in Gravesend (although the movie was not filmed there)

Brighton Beach, also known as “LittleOdessa” Chinatown Coney Island Gerritsen Beach Gravesend Homecrest Manhattan Beach Mapleton, Grays Farm Midwood Sea Gate Sheepshead Bay